Context Sharing: How MCP Opens A New AI UX Pattern for Shared Assistants

Rethinking how we collaborate with AI — from isolated prompts to collective understanding.

Zusammenfassung (Deutsch): In aktuellen KI-Interaktionen arbeitet jeder Nutzer in seiner eigenen isolierten Chat-Welt. Dieser Artikel stellt „Context Sharing“ als neues UX Pattern vor, inspiriert vom Model Context Protocol (MCP) von Anthropic und der psychologischen Theorie der Joint Action. Durch gemeinsames Teilen von Kontext – ähnlich wie bei gemeinsamen Google-Dokumenten oder Git-Versionierung – können mehrere Nutzer und KI-Assistenten nahtlos zusammenarbeiten. Dies könnte die derzeitigen fragmentierten KI-Nutzungsweisen verbessern und eine geteilte „kognitive Schnittstelle“ schaffen.

The Absurdity of Siloed AI Chats in Teams

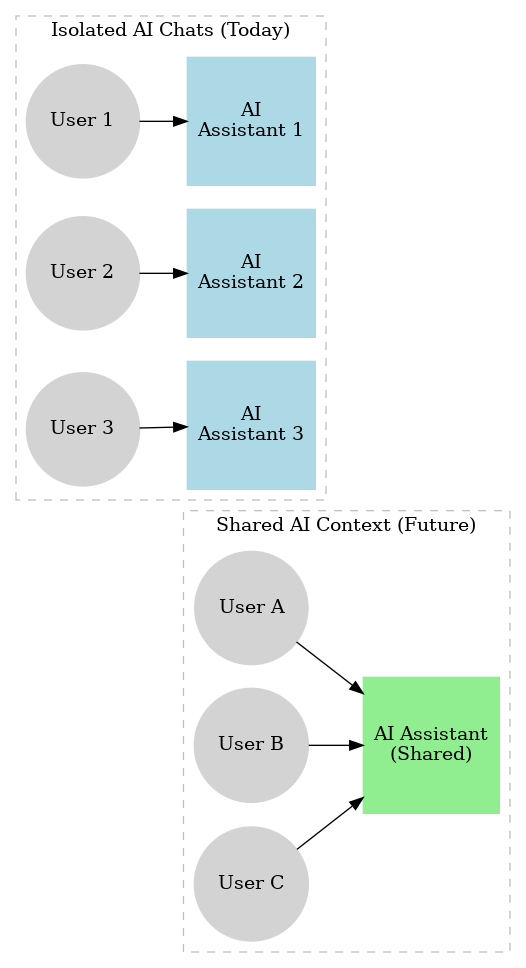

Imagine a team where each member has their own personal AI assistant, but none of those assistants can talk to each other or share notes. If Alice asks her AI a question, Bob’s AI remains clueless about it. Every user is stuck in a separate siloed chat, as if each had an intern with selective amnesia that cannot share or retain knowledge beyond their one-on-one conversation. This is essentially how most AI tools work today: by design, “each thread is completely isolated such that stuff a user writes isn’t shared with other threads” (Under one assistant, is context shared between threads? - API - OpenAI Developer Community). While isolating contexts is good for privacy, it becomes absurd for collaborative work. In a group project, team members often end up copy-pasting information between their individual AI chats, repeating the same prompts, and duplicating efforts. There is no shared memory or awareness across these AI assistants, leading to fragmented knowledge.

Why is this a problem? Because human collaboration thrives on shared context. When colleagues work together, they build on common knowledge, refer back to shared documents, and keep track of collective progress. Our current AI experience breaks this fundamental principle – it treats each user-AI interaction as a standalone bubble (besides project functionalities in the newest versions of GPT and co). The result: AI that doesn’t know what “we” already asked or discovered in a parallel chat, and cannot proactively assist the group as a whole. It’s like having multiple co-workers who never speak to each other, each reinventing the wheel.

Beyond Prompt Engineering and RAG: Stop Patching the Leaks

In response to these limitations, developers have tried to jury-rig solutions. Prompt engineering became popular – meticulously crafting and tweaking prompts to squeeze better answers out of an AI. Similarly, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG and the agentic systems too) has been used to inject relevant context into a prompt by fetching documents from a knowledge base. These techniques help in the short term, but they are band-aids rather than sustainable fixes. A Harvard Business Review piece bluntly noted that prompt engineering’s gains are limited by “lack of sustainability, versatility, and transferability” (AI Prompt Engineering Isn’t the Future). In collaborative settings, no matter how clever your prompt is, it has to be repeated for each user’s separate session. And RAG, while great for supplying facts, only provides a passive snippet of context to the model – it doesn’t enable the AI to truly remember and actively share evolving context over time (#14: What Is MCP, and Why Is Everyone – Suddenly!– Talking About It?). Essentially, RAG drops documents into the model’s input, but the model still lacks a persistent, shared memory across interactions.

Think of it this way: Prompt engineering and RAG are like giving each of those isolated interns (AI assistants) a cheat sheet right before they answer. It helps in the moment, but the next intern over has no idea what’s on your cheat sheet. There’s no long-term, communal learning happening. As AI deployments grow more complex, these patches buckle under scale – it’s impractical to maintain perfectly optimized prompts for every scenario or constantly update retrieval indices for every single user’s chat. We need a more robust architectural solution, not just prompt tweaks.

What Is Context Sharing?

Context sharing is a proposed new AI UX pattern that addresses this issue at its core. In simple terms, context sharing means multiple users and AI systems contributing to and drawing from a shared pool of knowledge in real-time. Instead of each user being tied to an isolated model instance with a blank-slate memory, users (and even multiple AI agents) would interface with a shared cognitive workspace. All relevant conversation history, documents, and decisions in this workspace are accessible to authorized participants. In effect, the AI assistant is no longer personal and siloed – it becomes a shared team assistant or a “collective intelligence” that everyone collaborates with together.

Contrast the two setups: today’s isolated chats versus a future with context sharing. In the isolated model, you have separate copies of an assistant for Alice, Bob, and Carol – none of which know what the others discussed. In a context-sharing model, Alice, Bob, and Carol might all chat with the same assistant agent, which has a joint memory of their interactions and knowledge base. The assistant can incorporate inputs from one user and use them to help another, just like a well-informed team member would.

This pattern opens the door to true multi-user collaboration with AI. For example, Alice could ask the assistant to summarize the project brief, Bob could follow up in the same thread to drill down on a specific point, and Carol could see that history and have the AI draft a combined report. The assistant isn’t starting from scratch with Carol – it has the shared context of Alice’s and Bob’s prior queries. Each user could define which part of the current context is relevant, which lacks detail – leading to an enhanced understanding of the matter by introducing domain and process knowledge of each user. In essence, the AI becomes a sort of shared brain supplementing the group. This is a fundamental shift in UX: from isolated AI chats to a persistent, shared conversational space.

Anchoring in Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP)

How do we actually enable context sharing? A big piece of the puzzle is infrastructure. One notable development pointing in this direction is Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP) – an open standard announced in late 2024. MCP isn’t explicitly about multi-user chats, but it provides the plumbing for shared context between AI systems and data sources. It’s described as “an open protocol that standardizes how agentic workflows and applications communicate and share context, resources, tools, prompt catalogs and more with one another.” (Introducing the Model Context Protocol \ Anthropic) In other words, MCP lets different components of an AI system speak a common language when exchanging context.

Why is this relevant? Because MCP tackles the fragmentation of information that plagues AI assistants. Prior to MCP, connecting an AI to various data (your documents, Slack, codebase, etc.) required bespoke integration for each app. Every new context source was a one-off effort, contributing to the “information silos” that keep models isolated. MCP replaces those siloed connectors with one universal interface. Suddenly, an AI agent can dynamically discover and plug into multiple context sources on the fly – no more lost threads or custom integrations when moving between tools.

For instance, with MCP an AI could fetch data from a Google Drive, then call an API, then update a database, all while maintaining a shared context across those actions (What Is MCP, and Why Is Everyone – Suddenly!– Talking About It?). This is crucial: the AI isn’t treating each tool interaction as a forgettable one-off; it carries over what it learned (state, results, user instructions) as it switches tasks. The AI community quickly recognized that this “context portability” is a game-changer. As one analysis put it, “MCP is a more general mechanism: where RAG gives passive context, MCP lets the model actively fetch or act on context through defined channels”.

Now, imagine extending that same principle to multiple users or agents sharing one model’s context. MCP already deals with sharing context between an AI and external knowledge sources; a logical next step is to share context between users or between multiple AI agents within a common session. In a multi-agent system, MCP could function like a blackboard or common memory that all agents read from and write to. Likewise, a multi-user AI assistant could use an MCP-like channel to ensure each user’s contributions update the same underlying context (rather than living in separate silos).

Anthropic’s push with MCP underscores a broader industry realization: context is too important to remain trapped in single-user silos. Whether it’s connecting AI to live data or connecting multiple participants to one AI, the goal is a unified context space where knowledge can flow securely and seamlessly. MCP provides a technical backbone for this vision, much like HTTP did for the web – it’s a connective layer. On top of that layer, we can build user experiences that feel like a shared AI assistant rather than dozens of isolated bots.

Real-World Analogs: Google Docs, Git, and Collaborative Interfaces

If context sharing still sounds abstract, consider some real-world analogies. Think about Google Docs: before cloud collaboration, teams would email around separate copies of a Word document – a nightmare of conflicting versions and lost changes. Google Docs introduced a single shared document in the cloud that everyone can edit together, seeing each other’s updates in real-time. The effect on productivity was dramatic; suddenly everyone literally “on the same page.” In a similar vein, software developers long ago adopted Git version control, which, despite being asynchronous, provides a shared history of code changes that anyone in the project can pull and contribute to. No developer works on code in total isolation anymore – there’s a continuous integration of contributions.

Now apply this mindset to AI assistants: Instead of each person working with a separate chatbot (the equivalent of separate Word files or code copies), we maintain a shared conversation or knowledge base that the AI and all humans reference. It’s like a Google Doc of dialogue or a Git repository of knowledge that the AI uses to “version control” the evolving context. Everyone sees (or at least the AI sees on everyone’s behalf) what questions have been asked and answered, which documents have been referenced, which decisions made.

This unlocks powerful collaborative workflows. For example, in a product design session, the whole team could brainstorm with a single AI whiteboard assistant. Alice sketches an idea and the AI generates some descriptions; Bob refines one of those descriptions further with the AI; Carol asks the AI to summarize the trade-offs discussed so far. The AI’s responses improve because it remembers the entire session’s context – much like a human facilitator would recall “Alice’s earlier point” and “Bob’s suggestion” when helping Carol. The shared assistant becomes an always-on participant in the group, one that “remembers everything that has been put on the shared board.”

Crucially, context sharing doesn’t mean chaos or lack of privacy. Just as Google Docs has permissions and version history, a shared AI context can be managed with access controls and transparency. Team members might have the ability to mark certain information as private to them, or the system could delineate which knowledge came from whom. But the default mode would be collaboration-first: we assume the AI is serving a group purpose, not just an individual. This is a shift in design thinking for AI products – treating the AI interface as a multi-user environment like a Slack channel or a multiplayer game, rather than a single-user app. It calls for new UI elements (e.g. indicating when the AI learned something from Alice vs. Bob) and new mental models for users (e.g. “chatting with our assistant” instead of my assistant). It’s a more complex design challenge, but one that aligns much better with how real teamwork happens.

Joint Action and Distributed Cognition: The Human Science of Shared Context

Why do we expect context sharing to make such a difference? Because human psychology tells us that shared context is the bedrock of effective collaboration. In cognitive science, Herbert H. Clark’s theory of common ground argues that people engaged in any joint activity must continuously establish and update a shared body of knowledge to coordinate effectively. Clark famously noted that in conversation, participants need mutual knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions – “individuals engaged in conversation must share knowledge in order to be understood and have a meaningful conversation”. This is true in everything from simple dialogues to complex team projects. When we work together, we create a collective context (“what we all know so far”) that guides our interactions.

Researchers call such tightly coupled collaboration joint action. As one paper succinctly put it: “People rarely act in isolation; instead, they constantly interact with and coordinate their actions with the people around them.” ( Joint Action: Mental Representations, Shared Information and General Mechanisms for Coordinating with Others - PMC ) If AI assistants are to participate in joint actions with humans, they too need access to this shared realm of information. An assistant that only knows what one person told it – and nothing about the surrounding joint activity – is fundamentally handicapped in a group setting. It can’t refer to “what you all decided in yesterday’s meeting” if that info lives only in someone else’s chat. In contrast, an AI plugged into a shared context can much more naturally take part in group workflows, because it has the common ground to do so.

The concept of distributed cognition reinforces this point. Distributed cognition (pioneered by Edwin Hutchins and others) is the idea that cognitive processes aren’t confined to an individual’s mind, but are spread across people, tools, and the environment. For example, the process of navigating a ship is not just in the navigator’s head – it’s in the team’s coordinated actions, their instruments, maps, and shared notes. Knowledge literally “lives” in the system of multiple people and artifacts (Distributed Cognition - The Decision Lab). In modern knowledge work, we see distributed cognition in how teams use external tools (like whiteboards, documents, workflow apps) to collectively store and process information. An AI assistant with context sharing essentially becomes another node in this distributed cognitive system – a very powerful one that can store, retrieve, and reason over the team’s shared knowledge.

By grounding AI interactions in theories of joint action and distributed cognition, we design technology that fits naturally into how people actually collaborate. Instead of forcing humans to adapt to AI’s limitations (e.g. constantly re-feeding context or working in parallel silos), we adapt the AI to human strengths – our ability to work together through shared understanding. Context sharing gives AI a seat at the table in the collective thinking process, aligning it with the social dynamics of teamwork. It means the AI can participate more like a real team member: listening to everyone, remembering the group’s history, and contributing relevantly at the right times.

Multi-Agent Synergy and Human-AI Alignment Implications

Context sharing isn’t just about multiple human users – it also extends to scenarios with multiple AI agents or tools working in concert. In cutting-edge AI systems, you might have a constellation of specialized agents (for example, different bots handling research, planning, execution, etc.) tackling a complex task. One of the hardest parts of orchestrating multi-agent AI is getting them to cooperate rather than step on each other’s toes or work with incomplete information. A shared context can act as the coordination medium for agents, much like a common whiteboard in a meeting. If all agents read from and write to a shared memory of the task state, they can synchronize efforts and maintain consistency. Indeed, this idea harks back to early AI blackboard architectures, where different knowledge sources would contribute to a common blackboard to solve problems collectively. Modern protocols like MCP are reviving this concept by allowing multiple tools/agents to operate through “a single interface” with a shared context state (How MCP can take AI agents to the next level? - Threads) (Building Scalable Financial Toolchains with Model Context Protocol ...).

Now consider human-AI alignment. Alignment is about ensuring AI systems act in accordance with human intentions and values. It’s often discussed in the context of a single AI aligning with a single user or an abstract human ideal. But in practical deployments, alignment will likely be a team sport: multiple humans supervising and collaborating with multiple AI components. Shared context could significantly improve alignment for a couple of reasons. First, transparency: when an AI’s knowledge and conversation logs are communal, it’s easier for humans to review what the AI has been “thinking” or where it might be going wrong. Misunderstandings or off-track assumptions can be caught by any team member because the state is visible to all, not hidden in an isolated chat. This creates a form of collective oversight – many eyes on the AI’s contributions, which is analogous to code review in software teams (many eyes make bugs shallow).

Second, consistency with shared values: in a shared context, the goals and constraints are laid out for all to see. The AI can be explicitly given the group’s objectives, decisions, and values as context. If the team collectively steers the AI when it produces an output that seems misaligned, that correction stays in the shared memory and benefits all future interactions. Over time, the AI assistant trained/fine-tuned in a context-sharing environment may better internalize the common values of the group it works with, leading to more aligned behavior. In contrast, if each person only corrects their own AI instance in isolation, those value corrections don’t propagate – the AI might repeat the same misalignment with the next user. Shared context makes alignment corrections cumulative and persistent across users.

There are of course challenges here: designing for privacy, preventing misuse of shared data, and ensuring the AI doesn’t inadvertently reveal something to one user that another wanted kept separate. These are solvable with careful UX and policy (for example, user-specific contexts could be layered under the global shared context, or the assistant could be clear about context provenance: “I recall Alice mentioned X earlier”). The upshot is that the potential benefits to teamwork and alignment are huge. Done right, a shared context assistant could become a force-multiplier for group intelligence, amplifying our ability to solve problems together while keeping the AI’s actions visible and on-track with human intent.

Toward Shared Cognitive Interfaces

The evolution of AI UX toward context sharing is an exciting, human-centric shift. It envisions AI not as a collection of isolated smart chatbots, but as a new medium for joint human-computer action. We started with each user talking to their own private model, which made sense in the early days of personal AI assistants. But as AI becomes woven into every collaborative process, that model is straining. The next leap is to create shared cognitive interfaces – spaces where humans and AI systems collectively build and use context. Miro is giving here the right impulses with their Innovation Workspace - approach.

Anthropic’s MCP is laying the groundwork by making context fluid and portable across systems. The psychology of joint action is reminding us that social coordination is key. And everyday tools like Google Docs show how empowering sharing is versus siloing. All these threads point to Context Sharing as a design principle whose time has come.

It’s about being human-centered and design-aware: recognizing that technology should augment our natural collaborative behaviors, not fragment them. By creating AI assistants with shared contexts, we move closer to AI that truly augments team cognition, acting as a partner that enhances how we work and think together.

The journey is just beginning. We need experiments, prototyping, and thoughtful design to get context sharing right. But the destination – AI that joins our shared conversations instead of splitting us into separate ones – is well worth striving for. It promises a future where an AI is not just my assistant or your assistant, but our assistant, seamlessly integrated into the collective efforts of humanity.

To move beyond siloed AI interactions, we need more than longer prompts or smarter models —

we need systems that understand and manage shared context as a first-class design concern.

If Context Sharing is to become a true UX pattern, it must address a wide set of challenges across three interconnected layers:

technical structure, social interaction, and cognitive support.

From Interface to Alignment: The Layers of AI Context Sharing

🛠️ Technical Layer

→ How do we build AI systems that carry context across time, tools, and teams?

Persistent Memory — Context must live beyond a single session.

Collaborative Access — Multiple people and agents need shared access.

Structured Relevance — Context should be machine- and human-readable.

Cross-Agent Compatibility — Context must move across tools and models.

Temporal Awareness — Context must adapt over time and remain relevant.

🤝 Social Layer

→ How do we reflect real-world collaboration, identity, and group intent in AI systems?

Identity & Intent Awareness — Who is involved, and why?

Granular Privacy Control — What is shared, with whom, and under what rules?

Conflict Resolution — How do we deal with contradictory instructions or inputs?

Social & Organizational Context — How do we align to teams, roles, and shared goals?

Attribution & Source Tracking — Where does information come from?

🧠 Cognitive Layer

→ How do we design context that supports, not overwhelms, human thinking?

Context Visualization — Can users see and understand what’s active?

Feedback & Correction Loops — Can users shape and refine shared memory?

Cognitive Load Management — Is the system enhancing clarity, not adding noise?

Context Curation UX — Can users easily pin, edit, and organize what matters?

Embodied Interaction Awareness — Does context include multimodal, human nuance?

Only when AI systems can share, shape, and sustain context like humans do —

can we begin to build truly collaborative, human-centered intelligence.

Sources

Context Sharing & Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP)

What is MCP, and why is everyone talking about it? (HuggingFace)Psychological Foundations of Joint Action

Joint Action: Mental Representations, Shared Information... (Frontiers / PMC)Distributed Cognition

Distributed Cognition – The Decision LabCritiques of Prompt Engineering & RAG

MCP and the Limits of RAG – HuggingFace